Monday, January 31, 2011

snow

Saturday, January 29, 2011

sharpening saw chain

"You can sharpen chainsaw chain?"

It was forehead-slapping moment. "You've never sharpened your chain before? What do you do when it gets dull?"

"Buy a new one? It's only a few dollars."

I'd have to forgive him for his ignorance. It wasn't exactly that he was too lazy, but rather that he honestly didn't know that saw chains were sharpenable. Still, I pressed the point. You don't go buy a new pocketknife every time it gets dull, even though it's only a few dollars, now do you? Since I figured that there are probably quite a few folks at home who probably didn't know about saw chain sharpening, either, I thought I'd write a little bit of instruction about it.

What you need:

- a round file, in the proper diameter for your saw

- a flat file; most any will do

- a depth gauge

- a vise is helpful, but not necessary

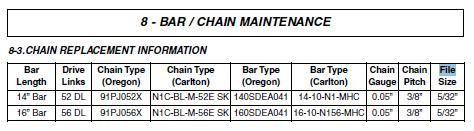

It's quite fast and easy to do. The most difficult part, in fact, might be figuring out what tools you need and finding a place to buy them. I'll walk you through that first. Your saw's operating manual should specify what diameter of round file your chain requires. Most Stihl and Husquevarna saws use a 7/32 file, but our McCullough needs 5/32. If you don't have your operating manual handy, you can search for your saw's make and model on the internet to download one. Some companies will even mail one to you, along with fun safety graphics. Here's a picture from my saw's .pdf manual:

Where can I find such a file, you might ask? We bought ours from our local hardware store. Some of the bigger chain stores might have them, or you can order them online. Or, if you're the kind of person who needs an excuse for random adventure, just drive down the road till you see a STIHL sign on somebody's workshop, barn, or storefront and ask them where to get one.

Any place that sells small round saw files probably also sells depth gauges. You'll only need one every third or fourth time you use the round file. The purpose of the depth gauge is to check the height of the raker -- the front part of your saw's tooth -- against the height of the actual cutting tooth. This difference in height is critical, because it controls how much wood the teeth chew off every time they pass through your log.

If you have a vise, set your saw's bar in it to hold the chain still while you sharpen. Take off the chain brake so you can spin the chain. It's wise to wear gloves so you don't nick your hands, although I usually don't bother. I marked the first tooth I sharpened with a blue sharpie. Use the round file to push from the inside, short edge of the cutting tooth to the outside. Pull the chain towards you to advance to the next tooth. Sharpen all the teeth on one side of the bar first, and then do the teeth on the other side. Our saw, which has been used for years without a single sharpening, still only needed about eight minutes of filing to bring it back to good-as-new.

If you have a vise, set your saw's bar in it to hold the chain still while you sharpen. Take off the chain brake so you can spin the chain. It's wise to wear gloves so you don't nick your hands, although I usually don't bother. I marked the first tooth I sharpened with a blue sharpie. Use the round file to push from the inside, short edge of the cutting tooth to the outside. Pull the chain towards you to advance to the next tooth. Sharpen all the teeth on one side of the bar first, and then do the teeth on the other side. Our saw, which has been used for years without a single sharpening, still only needed about eight minutes of filing to bring it back to good-as-new.About every third or fourth time you sharpen the teeth with the round file, you'll need to check the depth of the rakers. Set the depth gauge over your bar so that the high part is on the tall cutting edge of a chain tooth, and the raker is lined up with the groove. If the top of the raker sticks up over the top of the gauge, use the flat file to shorten it.

One of my favorite tools is the stump vise, pictured in orange. I discovered it while working as a sawyer for a wildland fire crew in North Carolina. The stump vise is designed to be small and light enough to ride around in your rucksack on the trail. When you need to sharpen your saw, you just pound the teeth into any nearby piece of stump or downed log, and it will hold your chainsaw bar still for you while you sharpen. It's been my experience that a saw chain benefits from a sharpening after about four hours of continuous use. If you're cutting all day on a fire or trail-maintenance crew, you can make two or three passes with the round file over each tooth while you're waiting for the saw to cool before you refill the gas tank. Enabling your saw to work harder makes you and your crew less fatigued.

One of my favorite tools is the stump vise, pictured in orange. I discovered it while working as a sawyer for a wildland fire crew in North Carolina. The stump vise is designed to be small and light enough to ride around in your rucksack on the trail. When you need to sharpen your saw, you just pound the teeth into any nearby piece of stump or downed log, and it will hold your chainsaw bar still for you while you sharpen. It's been my experience that a saw chain benefits from a sharpening after about four hours of continuous use. If you're cutting all day on a fire or trail-maintenance crew, you can make two or three passes with the round file over each tooth while you're waiting for the saw to cool before you refill the gas tank. Enabling your saw to work harder makes you and your crew less fatigued.While you're at it, run that flat file across the blade of your ax or maul, too. It's remarkably similar to sharpening a knife. Would anyone reading this like a more detailed explanation of how to do those things, too?

Friday, January 28, 2011

oh uncle sam, please protect us from the stoopid

-- Serenity Acres Now, "Is the Food Really That Unsafe?"

The linked blog post speaks about the USDA and Food Safety bills. He also notes that on an average farm, the farm itself contributes only 13% to the total household income. Makes me think of "hobby farm" in a whole new light.

yes, it's the same stuff, folks

"The blasts at the World Trade Center in 1993, Oklahoma City Federal Building in 1995 and on rush-hour London buses and trains in 2005 all contained ammonium nitrate fertilizer, which is manufactured in bulk as an explosive by the U.S. and other countries."

-- Scientific American "A Fertilizer Good for Only Growing Things, Not Destroying Them: New nonexplosive fertilizer could eliminate a deadly weapon from terrorists' arsenals."

Thursday, January 27, 2011

Rendering

Later this afternoon, I'll be trudging down the mountain with a clean 5-gallon pail in order to collect whatever's been held back for me. I'm excited. I'm so excited I'd leave right now, were it not for the fact that the Land Rover has again been spewing parts and fluid into the air, and T has taken my old reliable truck into town for work. That he works during the week and I work mostly on the weekends is almost as depressing as the idea that we might be deployed on opposite timescales. We each owe the Army just a little over a year, you see. He's scheduled to deploy this June and come back in 2012. I'm scheduled to leave in 2012, just about the time he's coming back. Sure, stop loss is supposed to be over and they can't deploy me when I have only three months left on my contract, right? Yeah. Let me know how that one works out for you.

I try not to think about the immediate future, actually. What keeps me motivated is seeing that little farm we don't own yet shimmering on the horizon, just waiting for the moment the military monster will let us out of its clutches. And in the meantime, I'll be doing things like learning to render fat. I must confess that "rendering" is a word I'm used to in the context of photography and Adobe digital editing. We're relying primarily on notes from a Foxfire book and YouTube videos for instruction. Hey, when it's free, you've got plenty of incentive to let yourself experiment.

There's a big dead Ponderosa Pine just next to our house, and our firewood stack is nearly empty. With any luck, it'll come down in the next few days. I'm a little nervous, as this will be the first big tree I've dropped so dangerously close to a structure. But we've got a plan of attack I'm satisfied with. Stay tuned.

Wednesday, January 26, 2011

a single 1940 apple

"While industrial agriculture has made tremendous strides in coaxing macronutrients -- calories -- from the land, it is becoming increasingly clear that these gains in food quantity have come at a cost to its quality. This probably shouldn't surprise us. Our food system has long devoted its energies to increasing yields and selling foods as cheaply as possible. It would be too much to hope those goals could be achieved sacrificing at least some of the nutritional quality of our food. As mentioned earlier, USDA figures show a decrease in the nutrient content of the 43 crops it has tracked since the 1950s. In one recent analysis, Vitamin C declined by 20%, iron by 15%, riboflavin by 38%, calcium by 16%. Government figures from England tell a similar story. Declines since the 50's of 10% or more in levels of iron, zinc, calcium, and selenium across a range of food crops. To put this in more concrete terms, you now have to eat three apples to get the same amount of iron as you would have gotten from a single 1940 apple, and you have to eat several more slices of bread to get your recommended daily allowance of zinc than you would have a century ago. These examples come from a recent report called Still No Free Lunch written by Brian Halweil, a researcher for World Watch, and published by The Organic Center, a research institute established by the organic food industry."

-- Michael Pollen, In Defense of Food

my future business partners

Her thick winter coat will leave clumps of hair wherever she scratches. Unkempt, perhaps, but clean. She'll nudge me, watching with her curious eyes, wondering what work we might have planned. Behind the corrugated tin wall of a loafing shed, her half-sister will regard us through one sleepy eye. She looks up only when I call to her, unwilling to disturb her doze unless absolutely necessary.

They'll be small for a team, maybe only fifteen and a half hands, with wide, smooth backs. I'll bring them into the lower level of our hillside barn. From above, we'll throw down hay when the sun goes down. For now, they stand quietly while I gather up gear. Shiny black working harnesses line one wall of a former box stall, each one lovingly cared for with saddle soap and neatsfoot oil and brasso on the fittings. I'll warm up their bits in my hands, and begin draping them in all the finery of a working trade. Come girls, let's get to work.

We'll walk out together into the woodlot, with a chainsaw, an axe, and a pouch full of felling wedges. Maybe someday I'll cut a tree or two with a crosscut saw, for fun or for demonstration, but today we have real work to do and but a few hours of daylight to do it in. We pick the ugliest trees, those crowding better-formed neighbors for sunlight or water. I find a hole in which to drop one. Then another. A peavy to help me roll the butt logs onto a length of chain, and then it's up to the girls.

Step, Big Mama. Step. One step at a time, till the chain draws tight. Draft-powered winch brings the logs up to the trail. We'll lift the heavy ends just off the ground, hanging from an arch that the horses can pull behind them like a small cart. And then it's away we go. Down the hill, past the cabin, past the barn. Right up to our own, cranky old sawmill, where we'll saw boards. A little draft power to help lift the heavy logs up onto the table. And then back for another. Good girls. I couldn't do this without you.

There's money in logging, to be sure, though surely not much. The demand for horse loggers, near as I can tell, greatly exceeds the supply. And we'll go out, someday, to someone else's farm, who will want their logs skidded up onto a truck to go to a mill and market. But we'll start on our own land, in our own woodlot, cutting our own trees to make our own boards. And maybe, just maybe, all that wood will be finished into fine furniture. A value-added product.

Two brown Suffolk mares. That's all I want.

Tuesday, January 25, 2011

revoking corporate personhood

The article gives an entertaining description of how we ever ended up with "The Total Weirdness of Corporate Personhood" in the first place.

Vermont Legislature Introduces Bill to Revoke Corporate Personhood

Monday, January 24, 2011

combat boots to cowboy boots

Combat Boots to Cowboy Boots may not have the most graceful moniker, but the program offers support for veterans needing an agriculture education. I found it through this article, which says:

"The program is an example of a new crop of nonprofits, college programs and a new office inside the U.S. Department of Agriculture that are all trying to ease a transition into the agricultural industry for young veterans."Apparently, similar programs are popping up all over the country.

If we don't have one in my hometown, I'm so going to start one.

The University of Nebraska's splash page for this program offers a quote which sums up my own philosophy on food security well:

“You can’t build a peaceful world on empty stomachs and human misery.”

- Norman Borlaug

Sunday, January 23, 2011

National Western Stock Show

This was the last weekend for the National Western Stock Show. Chose this weekend mainly because it featured the Draft Horse and Mule performances. I continue to be inspired by these magnificent animals. As we watched the Feed Team race and the Ladies' Cart class, I couldn't help but envision a team of my own. Not just a team, but a whole farm -- a crew of children to take to the shows, who could stand on ladders to groom; an antique sulky cart restored to all of its former glory; three matched teams of Suffolks, or perhaps Shires with their soft feathered pasterns. Nothing short of heaven. We talked animatedly about possibilities for logging, wedding carriages, hay rides, and animal-powered plows. Somewhere in the middle of the dreaming it surfaced that neither of us had much experience in driving. Leave it to reality to come in and burst a bubble.

This was the last weekend for the National Western Stock Show. Chose this weekend mainly because it featured the Draft Horse and Mule performances. I continue to be inspired by these magnificent animals. As we watched the Feed Team race and the Ladies' Cart class, I couldn't help but envision a team of my own. Not just a team, but a whole farm -- a crew of children to take to the shows, who could stand on ladders to groom; an antique sulky cart restored to all of its former glory; three matched teams of Suffolks, or perhaps Shires with their soft feathered pasterns. Nothing short of heaven. We talked animatedly about possibilities for logging, wedding carriages, hay rides, and animal-powered plows. Somewhere in the middle of the dreaming it surfaced that neither of us had much experience in driving. Leave it to reality to come in and burst a bubble.In all reality, though, what is now is just a shadow of what things can be as possibilities. The farm, at this moment, is but a small homestead with a few animals who are teaching us a great deal about caring for small stock, but not doing very much to earn their own keep. But the farm of the future can be anything we dream it, and each day brings us closer to making that dream a living, breathing, snorting reality. What should be the focus? Sure, we'll begin by clearing a little land, building a cabin or fixing up an old farm house, and putting a few chickens and goats out in the yard. But really, what should we raise? What will make us distinct, earn us our own keep, and fill us with joy into old age?

Finding somethi

ng that interests us is quite easy. The difficult part is narrowing it down to something to which we we can fully dedicate ourselves. As we passed rows of Buckeye hens and tiny bantam roosters with proportionately sized crows, we really want all of them. Every new creature we pass is a form of inspiration. What about shaggy Scottish Highland cattle, like the youngster you see here catching a quick snooze? They're still rare, but popular enough to have plenty of folks with whom to commiserate. But does that mean too many competitors? Figuring out the business aspects of running a small farm that can adequately support itself might just be the most daunting of all.

ng that interests us is quite easy. The difficult part is narrowing it down to something to which we we can fully dedicate ourselves. As we passed rows of Buckeye hens and tiny bantam roosters with proportionately sized crows, we really want all of them. Every new creature we pass is a form of inspiration. What about shaggy Scottish Highland cattle, like the youngster you see here catching a quick snooze? They're still rare, but popular enough to have plenty of folks with whom to commiserate. But does that mean too many competitors? Figuring out the business aspects of running a small farm that can adequately support itself might just be the most daunting of all.I expected to spend a little bit of hard-earned cash at the show, but what we mostly saw was a lot of glitter and gold that didn't appeal to us in the least. Barrel racers might need buckles the size of a Number 5 shoe and pink sequined blouses with matching saddle blank

ets, but our simple tastes weren't served by many of the booths. Cattle barons from all over the country come here to do business you know. All types of business.

ets, but our simple tastes weren't served by many of the booths. Cattle barons from all over the country come here to do business you know. All types of business.Across the back of the stadium where the sheepdog trials took place, CSA farmers from throughout Colorado spread their mid-winter offerings. We sampled the creamed honey and rubbed our fingers in the lotion testers, but our quest was specific: Apple Butter.

You see, earlier this year, we visited Connecticut to attend an old friend's wedding. (And to sleep in the park in New Haven... but that's a different story.) Part of the pre-nuptial festivities involved a visit to a local pick-your-own apple farm. My partner has quite the fancy for apple butter, which is as much a reminder of grandmother and home to him as it is an alien substance to me. We sorted through dozens of varieties to find the perfect Mason jar to bring home. But, as it turns out, apple butter has an evil side. Who knew that the Transportation Security Administration considered it a harborer of terrorism? It was confiscated at the airport as a dangerous substance. Colorado apple farms being conspicuously rare, we've had to go without.

Our pleas were answered when Grant Family Farms pulled us aside to offer us... apples. For free. And as it turns out, they're actually our very own local CSA. Who knew? What magical things serendipity can teach us.

Saturday, January 22, 2011

high-altitude bread

Just wanted everyone to know that, here at about 7,500 ft, the recipe turned out just fine and didn't require any adjustments for altitude or relative humidity.

Friday, January 21, 2011

environmental security

The U.N. University for Peace offers a Master's program in Environmental Security which fascinates me. I've found no U.S. master's program that comes close to considering the same subject material. Visions of spending a year in Costa Rica, talking with students from all over the world about the problems that face all of us, keep me from focusing on the things I have at hand to do right now. Just the course titles enchant me: NRD-6075 - Forestry, Forests and Poverty; NRD-6050 - Agriculture, Natural Resources and Sustainable Development; and GPB-6060 Gender and Human Rights.

The premise of the whole program is that mismanaged environmental resources are often the root causes of conflict. Take Darfur, for a modern example -- Sudanese factions have never particularly liked each other, but they weren't killing each other before there was drought and famine. Of course, it's never really quite that simple, but it's hard to deny that scarcities of basic necessities like drinking water exacerbate tensions.

Who else is thinking up solutions for these big-picture conflicts?

periodic instability

-- Paul Roberts, The End of Food

Thursday, January 20, 2011

Of course, they also kill people

-- Vandana Shiva

This quote is from an excellent 30 minute speech given by Vandana Shiva at a UU Church in San Francisco. Through the miracle of modern technology and the generosity of folks who don't believe in copyrighting ideas, you can download the entire speech and listen for free.

I think that most folks, at least within the activist community, are already aware that our good friend Monsanto is responsible for bringing us the pleasures of Agent Orange and DDT, in addition to handy household Round-Up. But everywhere I turn, I find more and more connections between the tools of warfare and those used, ostensibly at least, to create life in the form of food. If anyone out there knows of any existing books or research on this topic, I'd greatly appreciate if you pointed me towards it. Because, while little snippets appear everywhere, nowhere have I seen this phenomenon unified under one single heading. It's almost enough to make me want to write a master's thesis.

Wednesday, January 19, 2011

practical theory

-- Yogi Berra

I've always been intrigued by where stuff comes from and how it gets to us, but making a bookshelf from a tree inspired me to be a lot more vocal about it. After all, this is process is probably the most basic reason why the forestry industry exists in the first place. Your job, as a forester, is to grow trees that can become wood that can become furniture. It's a "value-added" process. But somewhere along the way, we became fragmented. The loggers who actually do the dangerous work of bringing those tall trees down to the ground as logs are somehow lower class, uneducated. It's your job, as the diploma-bedecked forester, to teach them the errors of their ways when necessary. And as a forester, it's also your job to keep your nose within your own lane. You don't worry about market conditions or sustainable consumer appetites. All you worry about, even when you talk about so-called "sustainable" forestry, is making sure the plot of ground you're responsible for puts out the same amount of quality wood as it did when you inherited it.

Doesn't that seem awfully short-sighted for a profession whose rotation plans often need to span into the hundreds of years?

And why are basic skills, like chainsaw felling, skidding, loading, and temporary road construction, relegated to optional classes like "Timber Harvesting Lab," rather than the centerpiece of the curriculum? What good does it do to come up with lengthy growth-ring histories and advanced statistical analysis of soil chemistry if you have no idea what applications that data may have to actual people, who are interested in utilizing actual trees?

How and why did our university agriculture education system -- the very system that spawned the land-grants that formed many of these universities in the first place -- get so far away from actually growing food and timber? When did it, like the media and government Farm Bills, become so married to the corporate model of production? Is there any place where traditional skills are still being passed from one generation to the next?

story of a bookshelf

See this bookshelf?

Picture it as a tree.

A gentle old ash, growing near the edge of a University football stadium parking lot, who spent nearly a century watching young people play. One day, lightning strikes, breaking one if its thick upper limbs. In the rounded stub that remains of its once mighty arm, birds nest, squirrels play, and rainstorm fury funnels through into the heartwood. Not tornadoes nor student drivers could bring down this old tree, but rot is a real threat. The decision is made, and the tree is painted for removal.

Enter the young forestry student. I was granted the privilege of taking down this tree because I was enrolled in an optional timber harvesting class. I felled it, with my borrowed Stihl 360 chainsaw and my much-respected instructor as my swamper and lookout. We loaded it onto a truck, brought it back to the portable sawmill to cut into rough-hewn boards, which were then dried. Stacking the kiln, one on one with a mentor like an old-time apprentice, is one of my fondest college memories. Busy hands free tongues to speak. We discussed why the moisture content of boards intended for use as studs, used outside the vapor barrier of a house as structural support, needs to be different than boards intended for use as fine furniture inside a house. We discussed how the decline of square dancing popularity has left the young people of my generation with few outlets to interact with potential mates in a wholesome and supervised way. This was the kind of knowledge I wanted from college, and I didn't realize at the time that colleges are rarely in the business of dispensing useful knowledge. I learned a trade, and I learned to soak up the wisdom of elders whenever they are willing to dispense it.

From the kiln the boards go to the jointer, where they are straightened, and the edges made perfectly 90 degrees from each other. This step, I learned, is skipped in most commercial wood processing facilities. They place their boards directly into the planer, a different machine which smooths each side, but does nothing to ensure their squareness. As my teacher said, "If they went in as crooked boards, they'll come out crooked, too." After the planer, my boards could be ripped into the sizes I actually wanted for my shelf. Making the boards, in fact -- the steps changing the wood from a log into the pieces I could screw together -- was the most difficult and time-consuming step in the whole process. When you go down to the hardware store and buy hardwood boards, you've already paid someone to do the majority of the work for you.

I graduated that semester, said my goodbyes, and trucked the finished boards home. The stain was the only part of the process that I didn't see the creation of myself. Piece by piece, it took shape, until the final bookcase you see in the first picture stood proudly in my living room. I didn't see the seed fall to the ground and grow into a young sapling. I didn't see the lightning that doomed that old grandparent to its day with the teeth of my chainsaw. But the pieces of the process that are influenced by humans, I got to trace, from forest to furniture.

I graduated that semester, said my goodbyes, and trucked the finished boards home. The stain was the only part of the process that I didn't see the creation of myself. Piece by piece, it took shape, until the final bookcase you see in the first picture stood proudly in my living room. I didn't see the seed fall to the ground and grow into a young sapling. I didn't see the lightning that doomed that old grandparent to its day with the teeth of my chainsaw. But the pieces of the process that are influenced by humans, I got to trace, from forest to furniture.That's the story of my bookshelf.